Photographer’s Distressing Photos Capture Life Inside El Salvador’s Notorious Prison

On March 15, photographer Philip Holsinger captured arguably 2025’s most sensational photographs when a group of Venezuelan prisoners arrived in El Salvador from the United States.

Their destination was CECOT — El Salvador’s notoriously strict mega-prison stocked full of gang members where inmates aren’t allowed visitors, or to go outside, and the lights are on 24 hours a day.

It was far from Holsinger’s first visit to CECOT, which stands for Terrorism Confinement Center. He had been in the country for over a year before the prison became the focus of an international news story.

“I came to El Salvador to investigate the country’s shocking transformation: what had been described to me by fellow journalists as the makings of a new police tyranny, but by others as a social miracle,” Holsinger tells PetaPixel. “I wanted to see it for myself.”

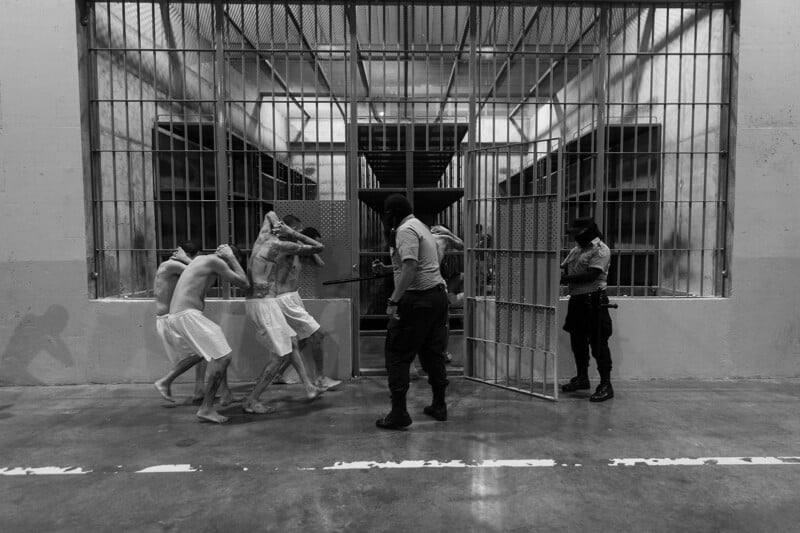

Holsinger was there before the planes from the U.S. arrived and photographed the entire transfer process, from the planes landing on the tarmac when there was a brief rebellion attempt, to the prisoner’s final transfer into one of the notorious CECOT cells.

“There was a total media blackout, only the El Salvador government comms team was there to document the event. But I was allowed to enter and photograph freely because I had spent much of the past year embedded with the military and police and they all knew me well,” Holsinger explains.

Holsinger’s year in the country enabled him to “develop deep relationships” and because of the photographer’s lack of regular social media updates, the Salvadoran government was happy for him to tag along, “even on sensitive missions.”

It was because this that Holsinger entered the airport compound with the government comms teams on March 15, accompanied the head of the prisoner transfer for the night, and was present when El Salvador officials greeted Homeland Security.

“The point is, I had existing trust and relationships that allowed me the ability to take action when the opportunity arose,” Holsinger says.

Holsinger describes the prisoner transfer as a “harsh procedure” but adds that it serves a purpose, “even if we don’t like it.” It involves folding the prisoners into “severe body postures”, shaving their heads, and stripping their clothes.

“The purpose of those severe body postures is actually standard operating procedure for moving dangerous captives—people who might be capable of killing you with their hands,” he explains.

“In a war zone or a police situation, soldiers and police are taught how to safely subdue, restrain, and move people in a way that keeps both the captive and the captor safe.”

Holsinger compares the process to a person entering military boot camp when the stripping down serves as a way to break down a soldier so they submit to authority.

“I do not say this to celebrate it but to put it in historical context. The problem is that whenever there are harsh tactics, they are easily abused,” he adds.

“And this is also the case with the procedures I witnessed on March 15. When the planes landed, at least two different groups on two different planes attempted to overthrow the planes.

“So when the guards were briefed at CECOT before the buses arrived, they were specifically instructed to let the prisoners know they were powerless, which became an invitation to push the limits, and some did.”

Although Holsinger had been in CECOT before, the night the Venezuelans from the U.S. were brought in was unlike his previous experiences.

“Up until that night I was used to seeing hardened, convicted killers being transferred to CECOT. The Venezuelans were different. Very different,” he explains.

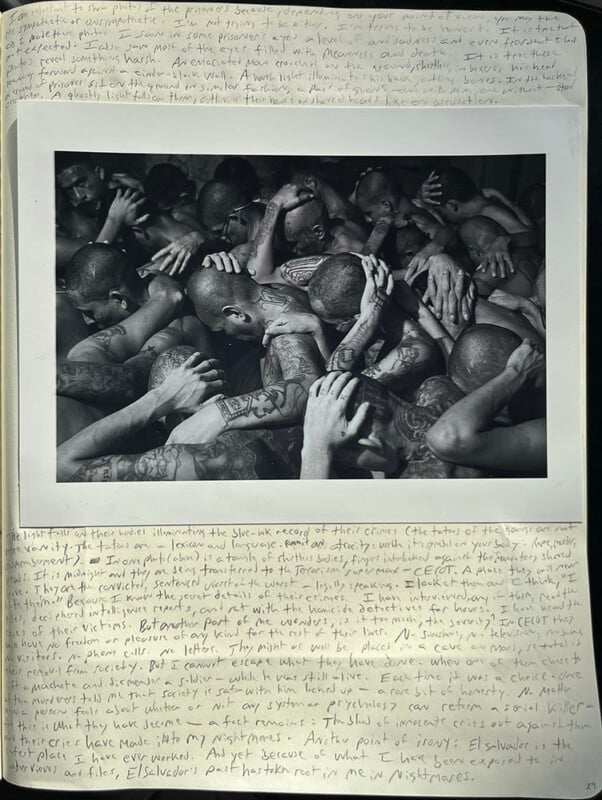

“And the fact that some of them seemed to be sincerely confused about why they were there led me to not only photograph their faces, but to record their cries. I thought, ‘if it is possible one of them is actually innocent then someone should know what I saw and heard so they can choose to investigate.’

“But I was not trying to be an advocate, and absolutely not trying to be an activist — which are things I do not agree with as a journalist, though some do.”

In an essay for TIME magazine, Holsinger wrote about one prisoner he witnessed in particular who cried out: “I’m not a gang member. I’m gay. I’m a barber.” Holsinger said he believed him. That prisoner was later named as Andry Hernandez Romero.

“I trust my judgment and I want to bring a reader beside me and point them to where I am looking, but I also do not believe my judgment is infallible,” he adds.

“When I wrote in the TIME essay that one of the Venezuelans claimed innocence and that in that moment I believed him, what I wanted to convey was his belief. I believe that he believed his innocence, which caused me to pause.”

Holsinger says he believes God placed him next to Romero for a reason.

“Imagine that with twenty buses and more than two hundred people, I ended up on his bus at that moment and heard his cries,” he adds.

“I know that may sound crazy, but after years of war and death, I can tell you I have seen mysterious, unexplainable things we call coincidences.”

Embedded in El Salvador

As mentioned earlier, Holsinger came to El Salvador to witness the country’s transformation from “the murder capital of the world” to what is now considered to be one of the safest countries in Central America.

“I decided I would move to El Salvador to photograph and research for a long-form magazine article, focusing on the security transformation, particularly the mass efforts for mass incarceration directed by the government’s ‘Territorial Control Plan’,” Holsinger says.

“After two months of working on what I thought would be a magazine article, I realized the material and experience were expansive enough to justify a book, so I committed to staying for a complete year to produce the book.”

Holsinger tells PetaPixel that he does not believe in “hit-and-run journalism.” Instead, he embraces the “old-fashioned methodology” employed by the likes of W. Eugene Smith at the now-defunct LIFE Magazine.

“I believe in getting to know secrets and real life rather than hearing speeches or inviting false narratives through traditional interviews,” he says.

“Of course, news and magazine reporting don’t generally have an economy for this form of deep embeds, so I fund my work through contract analysis and gallery sales of unique prints and handmade books.”

What is it Like Photographing Inside CECOT?

Part of his book will focus on specific murders that happened in the country and as part of that, he has been granted access to CECOT to speak with gang terrorists as part of the case study. He has gone back on multiple occasions to interview other killers who will appear in the book.

“I have also photographed two in-country mass transfers of convicted gang members to CECOT,” says Holsinger.

“Each transfer consisted of more than 2,000 prisoners and entailed dozens of hours of photographing along with government communications teams — no press allowed except myself.”

Holsinger says he has had an “unusual amount of freedom to photograph and observe” over a long period of time and he has faced “almost no restrictions.”

He tells PetaPixel that the convicted gang murderers do not hide their contempt for him and his camera. Holsinger has to be careful as the prisoners will “try to sneak in signs” in a bid to communicate to the outside world through sign language and even via their eyes.

Holsinger says because he generally doesn’t have tight deadlines, he prefers to shoot analog; he owns a Nikon F5, a Leica M6, a Contax, and a medium format Bronica.

He shot a lot of the Venezuelan prisoner photos with his Nikon digital cameras but prefers the problems of film cameras.

“Blur and focus issues make the photo feel like a physical thing. I do not like perfect photos because I want to feel the sense of being there. I want the viewer to feel like they are looking at a relic of a real event,” he adds.

Holsinger prints his photos and pastes his handwritten journals around them. He barely edits his photos and shoots in black and white for its “timelessness.”

Holsinger’s book on El Salvador remains in the production stage but watch this space. More of his work can be found on his Instagram and website.